CHAPTER XVIII

HOMELAND DEFENSE : BASIC PLANS AND PRELIMINARY

OPERATIONS

Strategic Situation-January 1945

As the year 1945 began, the Japanese nation faced disaster.1 The great decisive battle in the Philippines had been lost, and the enemy was moving on to invade Luzon, wresting from the Japanese their last operational base in the Philippines and extending the Allied air perimeter far out over Formosa, the China coast and southern Japan. Behind General MacArthur's forces hundreds of thousands of trained Army, Navy, and Air Force personnel were isolated, unable to contribute directly to the prosecution of the war. Ahead of the enemy, the road to the Japanese Homeland lay wide open.2

The war potential of the nation was at a record low. The backbone of both the fleet and the air forces had been broken in the Philippines, while the Army's ability to concentrate for a final effort was hampered by its commitments to many scattered and now isolated theaters. More serious than even the long chain of tactical defeats which had all but destroyed Japan's armed forces, however, was the rapid disintegration of the national war economy at its base.

Largely as a result of submarine interdiction of the South China Sea, the nation had already been deprived of essential strategic raw materials. Only in the early part of the war had Japanese shipbuilding facilities been able to keep up with sinkings by Allied submarines and planes. By January 1945, 69% of Japan's merchant fleet, including 59% of her vital oil tankers, had been sent to the bottom. Total gross cargo loadings in the quarter ending in December 1944 were a mere 33 of the wartime peak.3

As a result of the crisis in shipping, the flow of coal, iron ore, non-ferrous ores and concentrates, salt, and chemicals from the Asiatic continent had been materially reduced, while the supply of oil, rubber, nickel, chromium, and

[575]

aluminous concentrates from the southern area had slowed to a mere trickle.4 General MacArthur's seizure of Luzon and operations of the American carrier task force in the South China Sea gave notice that even this slender lifeline was about to be decisively severed.5

The collapse of Japan's overseas supply of raw materials was immediately reflected in the production figures of her basic industries. By early 1945, the iron and steel industry was operating at only about 49% of its wartime peak production, the three most important non-ferrous metals, copper, aluminum, and magnesium, were off 49% from their peak, and a similar situation obtained in the output of ferro-alloys. The chemical industry was producing at 62 of the first quarter of 1944, while the total production and import of crude and refined petroleum was down to a disastrous 26% in the quarter ending in December 1944. From the long-range strategic viewpoint, the situation had become hopeless.6

For their part, the Allies seemed to be in an extremely favorable position. In the European theater, the failure of the Germans' great Ardennes offensive presaged the defeat of Japan's distant ally, and it was a certainty that termination of hostilities in that area would be followed by the redeployment of overwhelming land, sea, and air power against Japan. Intelligence reports disclosed that the United States was rushing production of all types of amphibious

[576]

craft, heavy bombers, tanks, artillery, new rocket weapons, and fleet carriers.7 In the Philippines and the Marianas the enemy had excellent staging bases from which to launch the next effort.

In this disheartening atmosphere, Imperial General Headquarters undertook to determine the probable course of future Allied action. In general, it seemed clear that the United States would desire to bring the war to an early conclusion, and that the ultimate goal of enemy strategic policy would be the annihilation of the Japanese Army in the Homeland and the occupation of Japan. To prepare for the ultimate invasion, the High Command felt that the enemy would take the following course of action.8

1. Complete the occupation of key areas on Luzon as soon as possible.

2. Take one of the following courses of action given in order of probability:

a. A two pronged advance into the Homeland defense perimeter to secure advance bases and tighten the blockade of Japan Proper. The eastern advance would move from the Marianas into the Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands in February or March. On the west, a much heavier offensive would move from the Philippines to one or more key points bordering on the East China Sea including Formosa, the Nansei (Ryukyu) Islands, and the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, this operation to commence in March or April. The two prongs of the advance would converge in the final assault on the Homeland in the fall of 7945 at the earliest.

b. An advance from the central Pacific into the Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands and thence directly to the Homeland, (this operation to begin in February or March,) invasion of Japan Proper, in this case, to be in June or July.

3. In conjunction with operations on the southern approaches to the Homeland, the enemy would probably launch a secondary offensive from the Aleutians against the Chishima (Kurile) Islands in order to capture advance air bases.

A direct attack on Japan Proper without these preliminary steps was regarded as a remote possibility. Within the framework of the most probable Allied strategic plan, it was believed that Iwo Jima in the Bonin Islands would be the next invasion target, with Okinawa in the Ryukyus following soon thereafter.

An inventory of the forces available to meet the expected onslaught gave the High Command no cause for optimism. The basic compo sition and deployment of forces adopted for the Sho-Go operations still survived in principle, weakened and modified however by the heavy commitment to the Sho No. 1 front in the Philippines. Under Imperial General Head quarters there were two major commands responsible for the defense of the Homeland. The General Defense Command, under General Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni, was re sponsible for the air and ground defense of Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu, and the Izu Islands, and for a portion of the long-range air operations against enemy invasion convoys and bases. The Combined Fleet, under Admi-

[577]

PLATE NO. 141

Military Topography of Japan

[578-579]

ral Soemu Toyoda was responsible for all surface operations and the bulk of the long-range air operations over the approaches to the Homeland. (Plate No. 142)

Peripheral commands under Imperial General Headquarters included the Fifth Area Army under Lt. Gen. Kiichiro Higuchi, responsible for Hokkaido, the Kurile Islands, and Karafuto;9 Lt. Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi's Ogasawara Group in the Bonin Islands; and the Tenth Area Army under General Rikichi Ando, responsible for Formosa and the Ryukyu Islands.

For the land and air defense of Japan Proper (excluding Hokkaido and certain naval stations), the Commander-in-Chief, General Defense Command, had at his disposal the Western District Army (Lt. Gen. Isamu Yokoyama), responsible for Kyushu and southwest ern Honshu, the Central District Army (Lt. Gen. Masakazu Kawabe) in central Honshu and Shikoku, the Eastern District Army (General Keisuke Fujie) in northeast Honshu and the Izu Islands, the Thirty-sixth Army (Lt. Gen. Toshimichi Uemura) as a mobile reserve in the Kanto-Shizuoka area, and the newly-activated Sixth Air Army.10

To execute the Combined Fleet mission, the Commander-in-Chief had available Vice Adm. Seiichi Ito's Second Fleet, now engaged in

[580]

repair and training activities in the Hiroshima-Kure area11 and the Sixth Fleet under Vice Adm. Shigeyoshi Miwa, comprising Japan's 52 remaining submarines. For long-range offensive air operations Admiral Toyoda had at his disposal the Third Air Fleet under Vice Adm. Kimpei Teraoka in the home islands, the First Air Fleet under Vice Adm. Takijiro Onishi in Formosa,12 and Rear Adm. Chikao Yamamoto's 11th Air Flotilla, an independent unit, on Kyushu. Of these, only the latter was at this time in a state of real combat readiness.

With the disintegration of the Japanese surface forces, the burden of intercepting invasion threats against the Homeland fell almost exclusively on the air establishment. The air situation, however, was extremely discouraging. Only about 550 aircraft were available for offensive purposes. Distribution of strength was as follows:13

| Combined Fleet |

| First Air Fleet |

| Deployment: Formosa |

| Strength: 50 Aircraft |

| Third Air Fleet |

| Deployment: southwest Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu and the Ryukyus |

| Strength: 200 Aircraft |

| 11th Air Flotilla |

| Deployment: southern Kyushu |

| Strength: Navy-200 aircraft; attached Army-54 aircraft |

| General Defense Command |

| Sixth Air Army |

| Deployment: central and southwest Honshu |

| Strength: about 50 aircraft |

The situation in regard to defensive air strength, vitally needed to guard the Homeland against large-scale enemy air raids from newly-won bases, was equally bad.14 Available

[581]

PLATE NO. 142

Defensive Dispositions in the Homeland, 1 January 1945

[582]

for this purpose was a total of about 770 air craft and 1200 antiaircraft guns for all of Japan Proper (excluding Hokkaido). Air defense operations were decentralized, each District Army having under its command an air division for interceptor operations and a number of antiaircraft units. Disposition of the air strength attached from Sixth Air Army was as follows:15

Western District Army-12th Air Division

(111 aircraft)Central District Army-11th Air Division

(267 aircraft)Eastern District Army-10th Air Division

(288 aircraft)

In addition, the 302d, 332d, and 352d Naval Air Groups were attached to the Eastern, Central, and Western District Armies respectively for interceptor operations. This added about 100 fighters to the air defense system. These Army and Navy forces were concentrated principally in the Tokyo-Yokohama, Osaka-Kobe, and Shimonoseki-Moji areas, and around vital naval installations such as Yokosuka, Kure, and Sasebo.

Primary emphasis in the Sho No. 3 plan, formulated in the summer of 1944, had been placed on sea and air operations.16 As a result, the build-up of ground combat forces in Japan Proper during late 1944 had been on a very modest scale. A total of only eight divisions was available for operations in Japan Proper (excluding Hokkaido).17 The command system and deployment were as follows:18

Western District Army

86th Division-Miyakonojo, KyushuCentral District Army

44th Division-Osaka

73d Division-NagoyaEastern District Army

3d Imperial Guards Division-Tokyo

72d Division-Sendai

65th, 66th, aid 67th Independent Mixed Brigades -Izu IslandsThirty-sixth Army

81st Division-Utsunomiya

[583]

93d Division-Mt. Fuji area

4th Armored Division-Chiba and Narashino

Under the Sho No. 3 plan the mission of these units had been mainly the construction of coastal defense works in southern Kyushu, the Kanto plain, the Toyohashi-Hamamatsu area in central Honshu, and the Hachinohe district at the extreme northeastern tip of Honshu.19 At the beginning of the year, construction of semi-permanent artillery positions was on schedule. Construction of infantry positions, on the other hand, was lagging seriously. Only in the Ariake Bay area of southern Kyushu were they more than 40% complete. In the Toyohashi and Hachinohe districts, completion had only reached about 10%, while in the Kanto area, construction had just been started.20

In contrast to the small beginnings that had been made on the defenses of Japan Proper, strong ground formations had been disposed on the Homeland defense perimeter. On Formosa and the Ryukyus was the Tenth Area Army with a powerful force of eight divisions, seven independent mixed brigades, and an air division.21 The Ogasawara Islands were garrisoned by the Ogasawara Group, a heterogeneous combat formation built around the 109th Division.22

New Plans for Homeland Defense

By mid January 1945, the progress of events clearly indicated the need for a new and far-

[584]

reaching strategic plan to replace the now-defunct Sho-Go plan. In the pessimistic and confused official atmosphere of this period, further complicated by inter-service differences, it was difficult to formulate even the most general of policy directives.23 However, the need for action was imperative, and Imperial General Headquarters, on 19 January, submitted for Imperial sanction the draft of a general policy directive known as the "Outline of Army and Navy Operations." This directive, having been approved by the Emperor, was officially promulgated on 20 January and became the basis for all future Homeland defense planning.

Its essence was as follows:24

5. General Policy

a. The final decisive battle of the war will be waged in Japan Proper.

b. The armed forces of the Empire will prepare for this battle by immediately establishing a strong strategic position in depth within the confines of a national defense sphere delineated by the Bonin Islands, Formosa, the coastal sector of east China, and southern Korea.

c. The United States will now be considered Japan's principal enemy. Operational planning of all headquarters will be directed toward interception and destruction of American forces, all other theaters snd adversaries assuming secondary importance.

2. Preparation and Conduct of Operations

a. Resistance will continue in the Philippines so as to delay as long as possible the enemy's approach to the Homeland defense perimeter.

b. Key strongpoints to be developed within the perimeter defense zone include Iwo Jima, Formosa, Okinawa, the Shanghai district, and the south Korean coast. The main defensive effort will be made in the Ryukyus area. Preparations in the perimeter defense zone will be completed during February and March 1945.

c. When the enemy penetrates the defense zone, a campaign of attrition will be initiated to reduce his

[585]

preponderance in ships, aircraft, and men, to obstruct the establishment and use of advance bases, to undermine enemy morale, and thereby to seriously delay the final assault on Japan. The air forces will make a maximum effort over the perimeter defense zone. Enemy troops that succeed in getting ashore at points on the Homeland defense perimeter will be dealt with by those ground forces on the spot without reinforcement from other theaters.

d. Emphasis in ground preparations will be laid on Kyushu and Kanto. Strong air defenses will be established along key lines of communication, such as the Shimonoseki and Korea Straits, and at important ports and communications centers such as Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka-Kobe, and theMoji-Kokura-Yawata area.

e. During the delaying operations in the forward area, preparations for the decisive battle will be completed in Japan Proper by the early fall of 1945.

f. In general, Japanese air strength will be conserved until an enemy landing is actually underway on or within the defense sphere. The Allied invasion fleet will then be destroyed on the water, principally by sea and air special-attack units.

Pursuant to this basic policy directive, the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters assigned missions to its major subordinate commands as follows:25

1. The General Defense Command will secure the Homeland by destroying any enemy invading force. Emphasis in operational preparations will be on the Kyushu, Kanto, and Tokai26 districts. Efforts will be made to annihilate the Allied forces on the sea through the vigorous application of special-attack tactics.

2. The China Expeditionary Army will shift to a two front campaign and concentrate forces in the east and south China coastal sectors. It will secure the continental key area by destroying any enemy invading force. Main defensive effort will be in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River.

3. Southern Army will secure key points in the southern area and check the advance of the enemy toward the Homeland defense perimeter, thus facilitating the over-all operations.

4. Tenth Area Army will secure Formosa and the Ryukyus by destroying any enemy invading force.

5. Seventeenth Area Army27 will shift operational emphasis from northern to southern Korea and secure key sectors by destroying any enemy invading force.

On 30 January, the Navy Section of Imperial General Headquarters conducted a conference in Tokyo of the chiefs-of-staff of all fleets and naval districts. The "Outline of Army and Navy Operations" was presented to the conference and preliminary plans and general missions promulgated.

Immediately following the publication of the "Outline of Army and Navy Operation," joint conferences were held to iron out difficulties in the actual implementation of the plan. The first and most important problem was to formulate a sound and workable air policy. Efforts in that direction culminated on 6 February in the drafting of a Joint Army-Navy Air Agreement for the first half of 1945. This was to be subject to ratification by the two services

[586]

PLATE NO. 143

Facsimile of Imperial General Headquarters Navy Order No. 37, 20 January 1945

[587]

after study on the operational levels. In it essentials, the draft was as follows:28

1. All Army and Navy air forces in the Homeland (less air defense and training forces) will be concentrated in the East China Sea area (Formosa, the Ryukyus, east China, and Korea) during the months of February and March 1945. This concentrated air strength, together with air units already in Formosa (First Air Fleet and 8th Air Division), plus certain reinforcements from other theaters, enumerated below, will crush any enemy attempt to invade points within the aforementioned area.

2. Primary emphasis will be laid on the speedy activation, training, and mass employment of air special-attack units.

3. The main target of Army aircraft will be enemy transports and of Navy aircraft, carrier task forces.

4. Scheduled Strength (to be assembled by 1 April)

Army

Basic Force-1175 aircraft

Sixth Air Army-735

8th Air Division-440

Reinforcements-215 aircraft

from Fifth Air Army (China)-175

from Third Air Army (SE Asia)-40Navy (Tentative)

Basic Forces-400-580 aircraft

Third Air Fleet and Eleventh Air Flotilla-350-480

First Air Fleet-50-100

Reinforcements-125-175 aircraft

from China Area Fleet and

Thirteenth Air Fleet (SE Asia5. Command System: The basic command relationship will be one of inter-service cooperation. Coordination will be effected through Combined Fleet for the Navy air forces and through the General Defense Command and Tenth Area Army for the Army air forces.

On the same day that the draft of this joint agreement was issued, the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters published an implementing directive entitled "Outline of Air Operations in the East China Sea Area." In addition to the provisions of the joint agreement on which it was based, this plan contained detailed directions for the preservation and replenishment of existing units, strengthening of bases, and the redeployment necessary to bring the required air power into the theater by 1 April. This plan, designated the Ten-Go Operation Plan, became the basis for all future Army air operations over the East China Sea Area.29

To prepare for the forthcoming operations,

[588]

the Navy, on 10 February reorganized its air units within Japan Proper. The Third Air Fleet, with headquarters in the Kanto district, was relieved of all further responsibility for the Kyushu-Ryukyus area and assigned exclusively to operations in central and eastern Honshu. The Fifth Air Fleet was activated on Kyushu, absorbing the 11th Air Flotilla and all former Third Air Fleet units in the area. It assumed responsibility for future naval air operations in the East China Sea area under the joint agreement.30

For further implementation of the "Outline of Army and Navy Operations," Imperial General Headquarters quickly realized that reorganization and redeployment of the ground establishment was also imperative. Of first priority was the reorganization of the major commands in Japan Proper. This was accomplished by a War Ministry order of 22 January and an Imperial General Headquarters order of 6 February, which transferred the operational missions of the old district armies to a number of new area Army headquarters.31 New district Army commands were established in each area Army zone to assume responsibility for logistics and administrative matters.32 The General Defense Command was now constituted as follows: (Plate No. 144)33

Northeast Honshu

Eleventh Area Army-Lt. Gen. Teiichi Yoshimoto

Northeastern District Army Command-JendaiEast-Central Honshu

Twelfth Area Army-Gen. Keisuke Fujie

Eastern District Army Command-TokyoWest-Central Honshu

Thirteenth Area Army-Lt. Gen. Tasuku Okada

Tokai District Army Command-NagoyaWestern Honshu and Shikoku

Fifteenth Area Army-Lt. Gen. Masakazu Kawabe

Central District Army Command-OsakaKyushu

Sixteenth Area Army-Lt. Gen. Isamu Yokoyama

Western District Army Command-Fukuoka

[589]

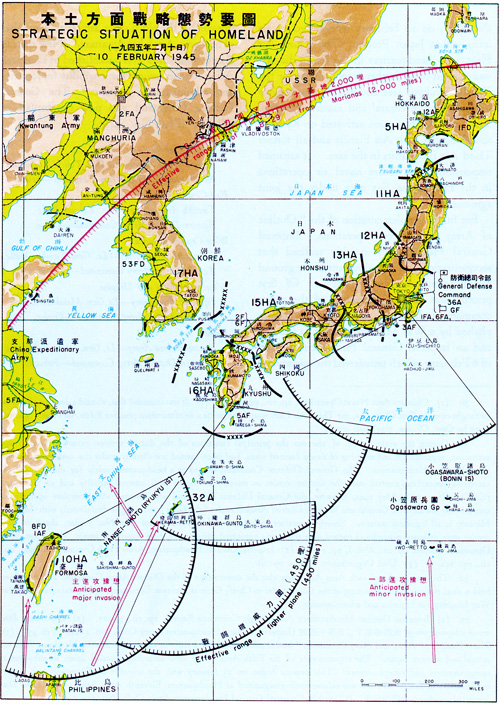

PLATE NO. 144

Strategic Situation of Homeland, 10 February 1945

[590]

Mobile Reserve-Kanto Plain

Thirty-sixth Army-Lt. Gen. Toshimichi Uemura

The reorganization of the high-level headquarters in Japan Proper was of course only a first step toward building up the ground combat forces. Although one division had been added to the Homeland forces on 22 January,34 there were still too few troops to garrison even the most critical points. Concurrently with the activation of the Homeland area armies, therefore, the Army High Command ordered the immediate organization of four independent mixed brigades as an emergency mobilization to fill the most critical gaps as rapidly as possible. These were as follows:35

95th Independent Mixed Brigade-Eleventh Area Army

96th Independent Mixed Brigade-Twelfth Area Army

97th Independent Mixed Brigade-Thirteenth Area Army

98th Independent Mixed Brigade-Sixteenth Area Army

Following this emergency measure, the Army undertook to establish a firm troop basis for the future Homeland defense armies. Discussions between the War Ministry and the High Command culminated on 26 February in the adoption of a plan calling for the mobilization of 42 divisions,18 independent mixed brigades,36 and six tank brigades, the bulk of this force to be added to the one armored and eight line combat divisions and seven independent mixed brigades at that time active in the General Defense Command. These units, together with the required logistic and administrative support elements, would contain a total of about 1,500,000 men. Mobilization of this enormous force was to be accomplished in three stages, the first from late February to early April, the second during April, and the last by the end of September. To provide the necessary high level headquarters, it was also planned to activate nine Army headquarters for tactical field command and two general Army headquarters to exercise command at Army group level. The activation schedule for units in the Homeland (less Hokkaido) was as follows:37

[591]

1. First Mobilization

13 coastal combat divisions38

1 independent mixed brigade2. Second Mobilization

2 general Army headquarters

8 Army headquarters

8 line combat divisions

6 tank brigades3. Third Mobilization

7 line combat divisions

9 coastal combat divisions

14 independent mixed brigades

In addition, during the period of the second mobilization, three line combat infantry divisions and one armored division were to be moved from Manchuria to the Homeland. This redeployment, together with the planned mobilizations, brought the projected total of Homeland (less Hokkaido) defense ground forces to a basic combat strength of 26 line combat divisions, 22 coastal combat divisions, and 21 independent mixed brigades.39 Armored composition was fixed at two armored divisions and six tank brigades.

The problem of supplying weapons and equipment to the new units was a serious one. However, when the mobilization plan was drafted, the total amount of weapons in the hands of Army ordnance supply, together with those to be produced during February and March plus weapons slated for transfer from the continent, was fortunately sufficient to permit a large enough initial issue to enable the units to begin their training.40 Provided production could be held at present levels, it was felt that the ordnance industry could fill the remaining combat equipment requirements by September. On this basis, the War Ministry set the following ordnance production targets for the period April through September:41

Rifles |

523,200 |

Light machine guns |

9,360 |

Machine guns |

1,260 |

Infantry cannon |

2,160 |

Antiaircraft guns |

606 |

Mortars |

3,300 |

Self-propelled cannon |

168 |

Light artillery |

178 |

Heavy artillery |

50 |

The production schedule for sea special-attack weapons was simultaneously set as follows:42

[592]

| Army Renraku-tei |

3,000 |

Navy |

3,840 |

Koryu and Kairyu (midget submarines) |

1,440 |

Kaiten (human torpedo) |

660 |

Aircraft production presented a special problem due to the concentrated attention being given the industry by enemy air units. Based on the assumption that production could be increased slightly over the average output in December and January,43 the Supreme War Direction Council adopted a figure of 16,000 planes as the goal for the period April through September.44 Production during the quarter ending in March was to be allocated exclusively to the Ten-Go Air Operation.

Attacks on the Homeland Defense

Perimeter

Long-range preparations for the defense of the Homeland had barely gotten underway when enemy attacks on the defense perimeter began. On 19 February, a powerful U. S. amphibious task force launched an invasion of Iwo Jima, keystone of the Ogasawara Island sector of the perimeter.

At the same time, the enemy violently accelerated the aerial offensive against Japan Proper, striking heavily at industrial targets and airfields in Tokyo, Osaka-Kobe, and Nagoya. From a total of 598 sorties flown over Japan Proper in January, Allied air activity rocketed to 3,193 sorties in February.45

To slow up the mounting American air offensive against Japan, it was imperative that the enemy be denied forward bases on the Homeland defense perimeter. Iwo Jima consequently assumed an importance far out of proportion to its actual size and facilities, because from its airfields enemy fighter planes would be able to fly both escort and attack missions over almost all of Japan Proper south of Sendai. (Plate No. 146)

Despite the importance of Iwo Jima, the Japanese were unable at this time to make any large-scale air commitment to its defense. The Ogasawara Islands did not afford a good chain of mutually supporting bases, and they were too far from Japan Proper. In any case, the Japanese air establishment was still in too debilitated a state to seek a decisive battle in the area. The defense of Iwo Jima therefore fell exclusively to the ground forces. For over a month Lt. Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi's Ogasawara Group (109th Division) held out against immensely superior American forces, fighting a tenacious battle in the many excellent caves and field fortifications on the island. By 22 March, despite this heroic resistance, Iwo Jima fell completely into enemy hands.46

As the campaign on the Homeland defense perimeter began, the enemy unleashed a series

[593]

of air attacks on large urban areas in the Homeland which rocked the nation to its very foundations. Switching from high explosives to incendiaries, the B-29's began these operations on the night of 9-10 March with a heavy raid on Tokyo. The new tactics caught the Japanese completely off guard, and the re sults were indescribably horrifying. Well over 250,000 houses were destroyed, rendering more than a million persons homeless, and 83,793 were burned to death.47 Between 10 and 17 March, raids on the same pattern were flown against Osaka, Kobe, and Nagoya. B-29 raids from November through February had been little more than an annoyance to the Japanese, but with the beginning of the fire-bomb campaign, enemy strategic bombing loomed for the first time as a threat to the entire social and economic fabric of the nation.

With the invasion of Iwo Jima and the sudden acceleration of the aerial offensive against Japan, it was clear that a move into the East China Sea area could not be far distant. The Navy, which had originally entertained considerable reservations about an air operation in that area before May, suddenly took steps to meet the emergency.

First of all, the Army-Navy Air Agreement of 6 February, which until now had been considered a highly tentative document, was formally ratified by the Navy High Command on 1 March. At the same time, plans were made to strengthen naval air participation in the forthcoming campaign. The 11th, 12th, and 13th Combined Air Training Groups were converted into operational units. To take over the new groups, Tenth Air Fleet was activated on 1 March in the Kanto district, Vice Adm. Minoru Maeda assuming command. The Third Air Fleet, whose mission under the original plans had been to garrison eastern Honshu and provide a reinforcement pool for the East China Sea air battle, was now informed that, upon the activation of the operation, it would immediately displace to Kyushu in full strength. Both the Third and Tenth Air Fleets were ordered to begin intensive training in special-attack methods. This training was to be completed by the end of April, when Tenth Air Fleet was also to move to Kyushu bases. The planned strength of Navy air units in the East China Sea operation was now fixed as follows:48

Fifth Air Fleet |

520 aircraft |

Third Air Fleet |

510 |

Tenth Air Fleet |

2000 |

First Air Fleet |

85 |

On 20 March, the Navy High Command issued an over-all policy directive which clearly set forth the basic concept of the Navy's participation in the Homeland defense campaign. This document, entitled the "Imperial Navy Outline Plan of Immediate Operations," contained the following general provisions:49

[594]

PLATE NO. 145

Civilian Air Raid Defense Activity: Women Fire-Fighters

[595]

1. The Ryukyu Islands are designated as the focal point of the decisive battle for the defense of the Homeland.

2. Special emphasis will be placed on the de struction of enemy ships by the prompt and vigorous use of sea and air special-attack forces.

3. Hit-and-run raids will be conducted against forward American attack bases to delay the launching of an enemy invasion of the East China Sea area.

4. At the same time, the defenses of the Homeland will be strengthened with emphasis on Kyushu and the Kanto area. Defenses at important straits and bay entrances will be strengthened. Sea routes to the continent will be protected.

Meanwhile, the preliminaries of the East China Sea air battle were already underway, giving the Japanese no time to complete their long-range preparations. Early on the morning of 17 March, Imperial General Headquarters learned through intelligence channels that sizeable American fleet elements had quit Ulithi atoll in the western Carolines. It was assumed that the enemy task force was on its way to attack the Kyushu area. The attack was expected the following day.

Combined Fleet immediately alerted Fifth Air Fleet in Kyushu. The Air Fleet commander, Vice Adm. Matome Ugaki, was ordered to attack the enemy task force only if it contained invasion transports and to refrain from an engagement if it was composed exclusively of warships.50 Vice Adm. Ugaki, however, feared that, if he did not attack, he would lose his entire command on the ground. He therefore forwarded a strong recommendation to Tokyo that counteraction be taken regardless of the composition of the task force. The High Command forthwith released the local commander from the earlier injunction and instructed him to use his own judgement.51

At 2300 on the 17th, a Fifth Air Fleet search mission detected by radar a large enemy task force barely 250 miles southeast of the southern tip of Kyushu.52 Vice Adm. Ugaki immediately issued orders for a dawn attack in force. Even as this strike mission was taking off, enemy carrier planes were swarming in to hit air bases in southern Kyushu and Shikoku. Heavy damage was sustained.53

During the next four days, a violent air battle raged over the southern Homeland. Fifth Air Fleet threw into the battle a total of 193 aircraft, including 69 tokko planes. Losses were staggering, amounting to 161 planes, or 83 per cent of the total aircraft committed. These losses, together with the widespread havoc caused by enemy attacks on airfields, left the Air Fleet powerless to participate in further large-scale action for several weeks to come. On the other hand, the damage

[596]

inflicted on the enemy was believed so severe that any immediate invasion threat to the East China Sea area was considered drastically reduced.54

Preparations to meet eventual invasion were nevertheless carried forward vigorously. Every effort was made to assemble the planned strength of 4,500 aircraft in the battle theater as rapidly as possible. On 21 March, Sixth Air Army, which was still engaged in displacing its main strength to Kyushu, was placed under the command of Combined Fleet. The Commander-in-Chief, Combined Fleet, now exercised unified command over the bulk of all Army and Navy air units operating in the East China Sea area.55

While the Japanese strove to complete these preparations, the enemy continued his air and sea blockade of the home islands, hampering deployment for battle and constantly whittling down the overall war potential of the nation. Enemy B-29's continued their immensely destructive incendiary campaign, now concentrating on Nagoya, Japan's chief aircraft production center.56

Late in March, the Superforts began a surprising new series of attacks which wrought havoc in the Homeland rear area. On the 27th and the 31st, they carried out attacks on the Kyushu bases of the Fifth Air Fleet, closing down each field several days for repair.57 On the 27th and 30th, they sowed thousands of aerial mines in Shimonoseki Strait and the western Inland Sea, closing that vital supply artery for an entire week.58

Submarines and aircraft also continued to take their murderous toll of Japanese shipping. By the end of March, 74% of the nation's total merchant tonnage had been sent to the bottom, including 75% of the tanker fleet.59 As the

[597]

shipping crisis deepened, transport of essential supplies to the southern Homeland battle theater became almost impossible.

On 23 March, a strong Allied carrier task force suddenly attacked the island of Okinawa in the Ryukyus. This attack immediately appeared to cast doubt on the Fifth Air Fleet's battle claims of 18-21 March. The High Command, however, took the sanguine view that this was merely a minor operation, undertaken by the enemy while en route back to Ulithi in retaliation for the losses he had suffered off the Kyushu coast.60

This serious misjudgement was quickly exposed on 25 March when the enemy began to put ashore a landing force on the Kerama Islands, a small group about 25 miles southwest of Okinawa. On the same day, Combined Fleet issued an alert for the Ten-Go air operation.61

The situation was now precarious. The commitment of the Fifth Air Fleet on 18 March, far from having delayed the enemy invasion, had actually resulted in a premature and largely ineffective expenditure of Japanese air strength in Kyushu. The Sixth Air Army and the Third Air Fleet had not yet completed their westward displacement, while the Tenth Air Fleet was just beginning its specialized training.62 Air reaction to the landings in the Ryukyus was therefore negligible. On i April, when the enemy extended the amphibious offensive to Okinawa, the burden of defending that important island fell initially on the ground forces alone.63

The battle on Okinawa went badly from the very beginning. Handicapped by insufficient troop strength,64 Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima, commander of the Thirty-second Army, had concentrated the bulk of his forces on the southern portion of the island, where the terrain was relatively favorable to a strong defense. This, however, left the central sector of the island, containing two valuable airfields, virtually unguarded. The enemy landed directly in this weakened sector and quickly mopped up the small security detachments stationed there. Lt. Gen. Ushijima's forces to the south dug themselves in on strong battle positions in the Naha-Shuri area. By the end of the second week of the campaign, enemy forward elements began to approach this line preparatory to a show-down battle.

Although continually harassed by enemy air raids on the Homeland, Combined Fleet finally succeeded during the first week in April in effecting a partial concentration of air forces in Kyushu. Execution of the Ten-Go operation then began in earnest.

The decisive air battle began on 6 April with

[598]

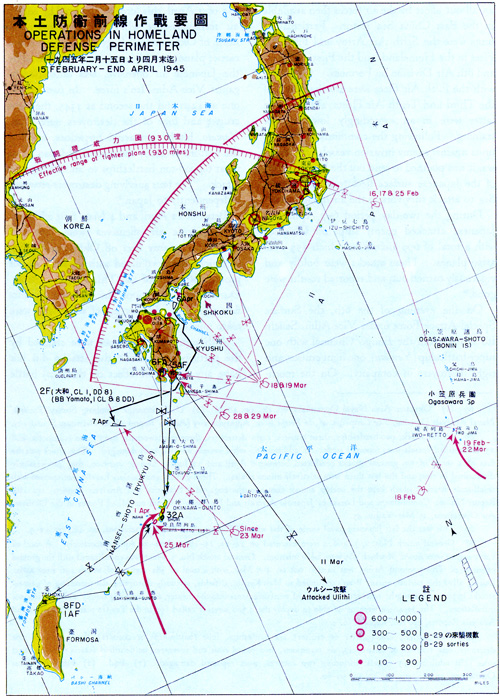

PLATE NO. 146

Operations in Homeland Defense Perimeter, 15 February-7 April 1945

[599]

an all-out effort by the air forces then available in the East China Sea sector. Participating units were the Sixth Air Army and Fifth Air Fleet in the Homeland, and the First Air Fleet and 8th Air Division on Formosa. Operating with the Fifth Air Fleet were attached units of the Third and Tenth Air Fleets, although the latter were in an exceedingly low state of training. Following the commitment of these units against enemy invasion vessels off Okinawa, it was planned to send out the last remnants of the Japanese surface fleet from the Inland Sea to attack survivors in the anchorage area.65

During the two-day period 6-7 April, the Japanese attacked enemy ships off Okinawa with a total of 699 aircraft, of which 355 were tokko planes. These attacks were boldly and vigorously carried out, and reported results were good.66

On the evening of the 6th, the Surface Special-Attack Force under Vice Adm. Seiichi Ito sortied from the Bungo Channel with one super-battleship (Yamato), one light cruiser, and eight destroyers in company. On the morning of 7 April, this force was spotted by enemy air reconnaissance while still over 400 miles north of Okinawa. A large part of the enemy's carrier plane strength, apparently undeterred by the Japanese air offensive, was unleashed against Vice Adm. Ito's force. In two strikes, one at 1240 and the second at 1345, the light cruiser and four of the destroyers were sunk. Yamato, hit by ten aerial torpedoes, went to the bottom at 1417, the second of Japan's two great 64,000-ton battleships to succumb to air attack. The four surviving destroyers returned independently to Japan.67

Between 12 April and 4 May, four additional large-scale air offensives were launched against the enemy fleet off Okinawa, the last of which was coordinated with the final all-out ground offensive of the Thirty-second Army During these operations, the Japanese air units flew a total of 1653 sorties, of which 761 were tokko missions.68

Although great successes were claimed by the participating units,69 the attacks did not have any noticeable effect on the local battle

[600]

situation. The Thirty-second Army ground offensive of 4-5 May made limited gains against exceedingly strong resistance, faltered, and fell back after a bloody two-day fight. Following this, Thirty-second Army was no longer capable of effective offensive action. Although the Ten-Go air operation was sustained for another six weeks, the enemy was securely in possession of Okinawa as a forward base after the failure of the 4 May offensive.70 All of Japan south of Tokyo, as well as Korea and the lower Yangtze, were now brought within easy range of enemy land-based fighters.

Just as the battle for control of the East China Sea area began, the Japanese High Command learned through intelligence channels that Soviet Russia had begun to redeploy troops from the European theater to the Far East. In Europe, the crossing of the Rhine by the Allied armies and the catastrophic defeats suffered by the Germans in the Saar and Ruhr valleys indicated that final collapse of Hitler's forces was imminent. Japan faced the dread of fighting the war alone.

Against the background of these alarming strategic developments, Homeland defense planning was hurriedly continued. On 20 March, Imperial General Headquarters Army Section transmitted to all major subordinate commands the preliminary draft of a voluminous operations plan to meet an invasion of the home islands. This document, based upon the general policy directive of 20 January, covered in considerable detail objectives, tactics and technique, troop movements, internal security, transportation, communications, and logistical administrative support. The draft was studied by subordinate headquarters, revised by the Army Section, and submitted to the Navy and to various governmental agencies for concurrence.71 On 8 April it was formally disseminated to the field commands. Its essential points were as follows:72

1. The forthcoming decisive operation in the Homeland and adjacent areas will be referred to as the Ketsu-Go Operation. Designations of the component operations will be as follows:

Ketsu No. 1 Hokkaido, Karafuto, and the Kurile Islands

No. 2 Northern Honshu

No. 3 Kanto District

No. 4 Nagoya-Shizuoka area

No. 5 Western Honshu and Shikoku No. 6 Kyushu

No. 7 Korea

[601]

PLATE NO. 147

Facsimile of Imperial General Headquarters Army Order No. 1299, 8 April 1945

[602]

2. Operational Policy

a. The Imperial Army will hasten preparations to meet and crush the attack of U. S. forces in the above key areas. Emphasis will be on the Kanto area (Ketsu No. 3) and Kyushu (Ketsu No. 6).

b. Preparations for operations prescribed in this plan will fall into the following general phases:

First April through July

Second August through September

Third from 1 October

Emergency preparations in Kyushu will be completed by early June. Dispositions will continue to be strengthened during the second phase, and all tactical plans completed. Final deployment of field units and perfection of the field positions will be completed in the early part of the third phase.

c. Air Operations

(1) A close watch will be maintained over all enemy fleet movements, particularly transport convoys. Air search over the approaches to the Homeland will be continuous and aggressive.

(2) Enemy amphibious task forces attempting to invade the Homeland will be destroyed on the water.

(3) The primary target of the air offensive will be transports.

(4) All air operations will be curtailed rigorously until the enemy main convoy approaches. Fighting strength will be preserved until the moment for the decisive effort.73

(5) Air support for ground forces will be restricted to liaison missions and tactical reconnaissance in extreme emergencies.

(6) Long-range, surprise air raids against such enemy bases as Iwo Jima and Okinawa will be carried out.

d. Ground Operations

(1) The ground forces will win the final decision by overwhelming and annihilating the enemy landing force in the coastal area before the beachhead is secure.

(2) Speedy maneuver of the largest possible force against the enemy landing sector is the key to success in such operations. As many local reserves as possible must be maneuvered into the expected landing sector as soon as it becomes known that the enemy intends to land. After the enemy has landed, additional ground troops from other parts of the Homeland will be deployed to the area in accordance with the plan prescribed in Para. 3 below.

(3) In the event of simultaneous invasions of more than one area, the main Japanese counteroffensive will be directed at the main enemy landing. Delaying actions will be fought in other localities. This principle will apply both tactically and strategically.

(4) If the location of the enemy's main landing is undetermined, the main Japanese force will be committed in the area which presents the most favorable terrain for offensive operations. Delaying actions will be conducted in other localities. This principle will apply both tactically and strategically.

(5) Large-scale and thorough construction of fortifications will be carried out with emphasis on those field positions designed to provide jumping-off, rallying, and support points for local

[603]

offensives.

(6) Special security precautions will be taken at vital installations to forestall enemy airborne penetrations.

e. Air Defense

(1) Air defense of the Homeland will be emphasized. Points of first priority will be Tokyo, cities lying on the principal routes of communication, vital industrial facilities, airfields and munitions dumps.

(2) Increasing emphasis will be placed on air raid precautions and perfecting warning facilities.

(3) Dispersal of facilities, particularly airfields, will be accomplished wherever possible.

(4) When the ground armies initiate their operational movements to counter enemy landings, their assembly must be covered. by antiaircraft units. Plans will be made for the large-scale diversion of such units to this mission at the appropriate time.

f. Channel Defense

(1) In cooperation with the Navy, the defenses of such important straits as Bun go, Kii, and Shimonoseki will be strengthened. Principal harbors will also be strongly defended.

(2) Batteries will be stationed so as to prevent penetration by enemy vessels and amphibious landings. Channel defense units will strengthen bomb and shell-proof installations, and will dispose armed boats at strategic points.

g. Guerrilla Resistance and Internal Security

(1) We will strive to realize our operational objectives through exploitation of the traditional spirit of "Every citizen a soldier."

(2) Guerrilla resistance will aim at the obstruction of enemy activities and the attrition of enemy strength through guerrilla warfare, espionage, deception, raids on rear areas, and demolition of enemy installations. Such resistance will be carried out as part of the overall operation to assist line units, to meet enemy airborne operations and small secondary amphibious landings, and to cut off and harass enemy elements which penetrate into the interior.

(3) Internal security will aim at protecting military activities, vital communications, transport, power sources, and secret areas. If necessary, internal security will quell public disorder arising as a result of air raids, bombardment, invasion, propaganda, and natural disaster.

(4) Forces for guerrilla resistance and internal security will be drawn from the entire body of the citizenry as the situation may dictate. Guard units and civilian defense organizations will provide manpower, organized around small elements of the field forces as a guiding nucleus. Such units will be under the command of the various district army commands.

3. Redeployment Plan74

a. In event of an enemy invasion of Kyushu, the following steps will be taken:

(1) Four line combat divisions will be dispatched to Sixteenth Area Army from forces available to Thirteenth and Fifteenth Area Armies in central and western Honshu and Shikoku.

(2) Preparations will be made for the advance of a second increment. Three or four additional

[604]

divisions will be dispatched from the Eleventh Area Army in northern Honshu and from Twelfth Area Army in the Kanto district to the Osaka-Kobe area, where they will be held in readiness for further advance to Kyushu.

b. In event of an enemy landing in the Kanto district, without a prior landing in other areas, the following steps will be taken:

(1) Three line combat divisions from Eleventh Area Army in northern Honshu, three from Fifteenth Area Army in the Osaka-Kobe area, and two from Sixteenth Area Army in Kyushu will be immediately sent to Twelfth Area Army and held in readiness in Nagano Prefecture as a mass counterattack force.

(2) If the situation permits, two line combat divisions will be speedily dispatched by Thirteenth Area Army from the Nagoya area to Twelfth Area Army in the Kan to district.

(3) Preparations will be made for the advance of a second increment. Two line combat divisions will be sent by Fifth Area Army in Hokkaido to Eleventh Area Army in northern Honshu, and five divisions from Sixteenth Area Army on Kyushu to Fifteenth Area Army in the Osaka-Kobe district, all these divisions to be held in readiness for further advance to the Kanto district.

4. Logistics Plan

a. General Aims

(1) The Homeland will immediately enter the status of a battle theater communications zone.

(2) Emergency logistic preparations called for under this plan will be completed by the end of June. The full program will be perfected by the end of October.

(3) Successful completion of this program is dependent upon securing maximum efficiency in production and procurement, use of transportation facilities, security of logistics installations, dispersal operations, transfer of service units and supplies from the Continent,75 and maximum utilization of idle materials.

(4) In order to meet the expected gradual increase in pressure upon land and sea transportation services, self-sufficiency in each district and area Army will be emphasized, particularly as regards food, materiel repair, and certain classes of arms and equipment procurement.

(5) The logistics base (excluding Korea) will be 2,903,000 men, 292,000 horses, and 27,500 motor vehicles.

b. Logistics Build-up

(1) As far as items of organizational equipment are concerned, the furnishing of new troop units will have top emergency priority over all other supply activities, emphasis being placed on units in the Kanto area and Kyushu.

(2) The over-all build-up targets for expendable items (excluding the normal unit allowance) will be, in the case of ammunition, enough for one campaign by the entire projected field strength (2,000 tons per division), and of fuel, food, and forage, enough for 1½ months of combat operations.76 The main stockpiling areas will be the Kanto and Kyushu areas.

(3) Only in Kyushu and the Kanto will the full ammunition unit of one campaign be available in operational stockpiles. Other areas will have such fractions of one unit as are prescribed.

[605]

PLATE NO. 148

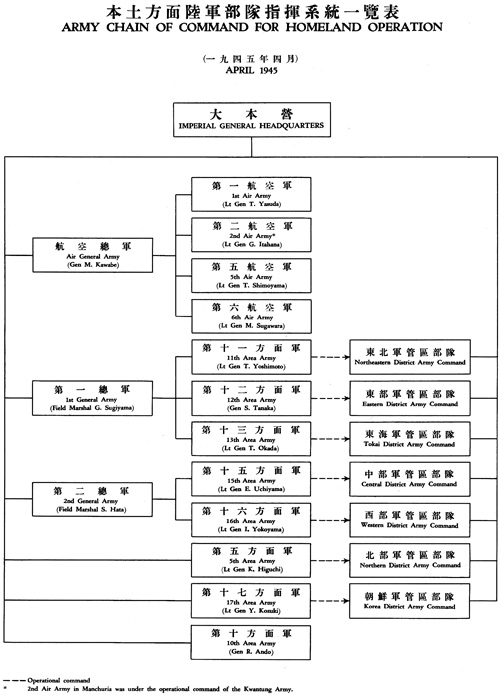

Army Chain of Command for Homeland Operation, April 1945

[606]

All main operational areas will have one month's supply of items of continuous issue. Certain remote areas may have larger stockpiles as prescribed.77

(4) Certain reserve stockpiles in all categories of supplies will be established by Imperial General Headquarters. Such supplies will be held available for rapid transfer to the active battle theater when it develops.78

c. Completion Deadlines

(1) Operational stockpiling in Kyushu and the Kanto: 31 May

(2) Operational stockpiling in other areas: 30 June

(3) Reserve stockpiling in Kyushu and the Kanto: 31 August

(4) Reserve stockpiling in other areas: 31 October

d. Redeployment of Supplies

(1) At the commencement of the operation, operational supplies will be released to the engaged units immediately in sufficient quantity to raise the supply level of the active theater up to two campaigns in ammunition and four months supply of fuel, forage, and rations.

(2) Supplies will be released from the reserve by Imperial General Headquarters as the situation requires.

e. Air Logistics

(1) Emphasis will be placed on expanding facilities for aircraft maintenance, preparation of ordnance for special-attack units, and dispersal of fuel dumps.

(2) Special-attack units will have first priority in all matters of supply.

(3) With two sorties per unit as the buildup target, bombs will be delivered and stockpiling completed by 30 June.79

Concurrently with the publication of the Ketsu-Go plan, Imperial General Headquarters activated the headquarters of the First and Second General Armies according to previous plan, simultaneously deactivating the General Defense Command. (Plate No. 148) The First General Army under Field Marshal Sugiyama established headquarters in Tokyo and assumed command of the Eleventh, Twelfth, and Thirteenth Area Armies.80 The headquarters of the Second General Army under Field Marshal Shunroku Hata was established at Hiroshima and included command of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Area Armies.81 To provide a similar command level for all Army air units participating in the campaign, an Air General Army headquarters was established under General Masakazu Kawabe. This headquarters took complete command of all Army air units in Japan and Korea,82 except the

[607]

Sixth Air Army which, until the completion of the Ten-Go operation, was to remain under the operational command of Combined Fleet. The organization of all these headquarters was completed by 15 April.

Meanwhile, the first general mobilization called for in the 26 February plan was successfully carried out. Thirteen new divisions, all of the coastal combat type, and one new independent mixed brigade were activated and assigned as follows:83

First General Army

Eleventh Area Army

142d Division

157th Division

Twelfth Area Army

140th Division

151st Division

152d Division

Thirteenth Area Army

143d Division

153d Division

Second General Army

Fifteenth Area Army

144th Division

155th Division

Sixteenth Area Army

145th Division

146th Division

154th Division

156th Division

107th Independent Mixed Brigade

On 8 April, concurrently with the publication of the Kestu-Go plan, the High Command also issued the text of an Army-Navy Joint Agreement regarding ground operations. This document contained the following general provisions:84

I. It shall be the general rule that the Army will take charge of land operations and the Navy of sea operations, both surface and underwater. Provisions for air operations will be set forth separately.85

2. The Commanders of the First General Army, Second General Army, and Fifth Area Army, hereinafter referred to as the senior commander(s) of the Army forces concerned, will be in command of all land operations in their respective zones of responsibility, including those conducted by naval troops.

3. All land operations at naval bases and naval stations will be under the immediate command of the commandant of the appropriate naval station. This officer will in turn come under the senior commander of the Army forces concerned.

4. During the period of operational preparations, the senior commander(s) of the Army forces concerned are empowered to issue general instructions to naval land troops concerning security, defense plans, tactics, and training.

5. Designated Army coastal installations in the vicinity of large naval bases will be placed under local navy command.

[608]

6. Upon activation of the operation, the Navy (Army) ground antiaircraft units in the zone of oper ations of Army (Navy) ground units will be placed under the appropriate Army (Navy) commander.

7. Sea and air special-attack bases will be de fended against land attack by the service operating the base. However, upon activation of the operation, such defense troops will be placed under the command of the Army or Navy commander controlling ground operations in the area concerned.

8. Local agreements necessary to carry out this general agreement will be concluded immediately.

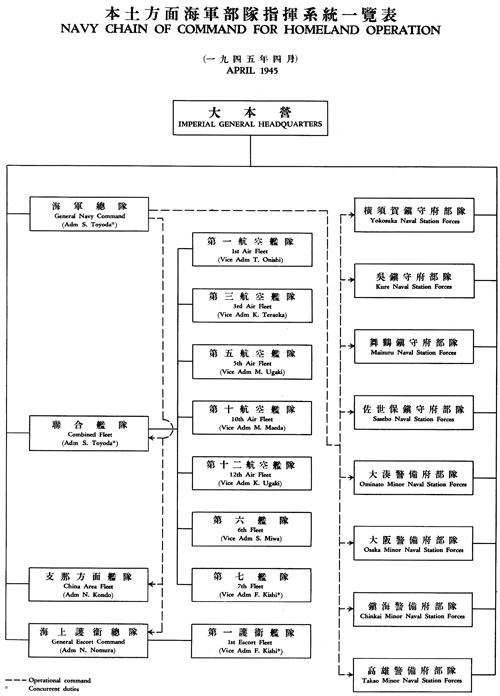

Following the adoption of this joint agreement, the Navy, on 25 April, established a General Navy Command to exercise supreme operational control of all Navy surface and air forces. Admiral Soemu Toyoda, Commander-in-Chief of Combined Fleet, was designated Commander-in-Chief, General Navy Command, holding both positions simultaneously.86 (Plate No. 149)

The wholesale mobilization of the national potential required to implement the Ketsu-Go plan obliged Imperial General Headquarters to give the nation frank warning that the Japanese home islands, inviolate through centuries, now stood in imminent peril of feeling the tread of an invader's heel. This dread prospect evoked in the Armed Forces and civil population alike a readiness to take the most extraordinary measures to repel the enemy.

The national attitude became the basis of tactical policy This was gradually elaborated in many official directives, guidance manuals and public announcements issued to implement the Ketsu-Go plan. The general concept of Homeland defense set forth in these documents was as follows:87

1. Phase I-Prior to Sortie of Enemy Convoy

a. The Fleet submarine force will disrupt enemy communications in the Marshalls, the Marianas, the Philippines, and the Ryukyus Islands areas. Submarine-launched aircraft will attack enemy forward bases such as Ulithi.88

b. Long-distance surprise air raids will be launched against enemy advance bases such as Ulithi, Iwo Jima, and Guam.

2. Phase II-After Sortie of Enemy Convoy

a. When the advance elements of the enemy invasion talk force enter the outer Japanese air perimeter, long-range Navy bombers will attack them vigorously, and short-range submarines will launch torpedo attacks.

b. When the main invasion convoy reaches a point 180-200 miles off Japan, the massed strength of all Army and Navy air tokko will begin to be committed. Koryu (midget submarines) will also join the attack.

c. As soon as the target and time of landing have been determined, airborne raids will be carried out against forward enemy air bases supporting the

[609]

PLATE NO. 149

Navy Chain of Command for Homeland Operation, April 1945

[610]

invasion. The purpose of these attacks will be to disrupt enemy air activity and thus facilitate Japanese special-attack operations.

3. Phase III-After Arrival of Enemy Convoy

a. When the convoy is in the process of anchoring, Koryu (midget submarines) will attack in force.

b. Kaiten (human torpedo will strike in force at gunfire support ships and transports.

c. The anchorage will be kept under constant interdiction, particularly at night, by means of attacks by Shinyo and Renraku-tei (crash-boats.

d. Long-range artillery will shell the an-chorage.

e. The air tokko offensive will continue.

f. While the enemy is engaged in ship-to- shore movement, transports and landing craft will be swept with fire by all available artillery strength.

4. Phase IV After Enemy Troop Landing

a. The artillery will shift its fire from waterborne targets to the landing beaches.

b. Air and sea special-attack forces will continue their attacks.

c. Infantry units of the coastal combat divisions will counterattack the invaders immediately from positions close to the beach. These counterattacks will be persistent and continuous so as to disrupt the consolidation of the beachhead and merge the lines in a confused struggle in which enemy air, artillery, and naval gunfire will be seriously hampered in choice of targets.

d. As soon as the enemy objective has been determined, the line combat divisions making up the decisive battle reserve will move into the main attack area and will occupy previously prepared jump-off positions. Tanks, heavy artillery, and other elements will be committed upon arrival in the forward area without waiting for the assembly of the entire counterattack force. Units will be fed into the battle as they arrive. They will be committed on a narrow front and in great depth against a thin enemy beachhead, already weakened by the activities of the coastal combat groups. These attacks will be continuous as long as there are units available in the rear areas. If properly executed, they will result in the complete collapse of the beachhead before the enemy has a chance to get ashore his heavy striking elements.89

e. Should enemy elements succeed in penetrating into the interior, they will be met with fierce and determined guerrilla resistance.

Under this general scheme of tactics, the chief burden of blunting the American invasion spearhead fell upon the air and sea special-attack forces. However, the application of the tokko principle was to be carried much farther than ever before. For the first time in the war, tokko methods were to be used in ground combat on a large scale, by both formal military organizations and partisan groups.

In land combat operations, the tank was the enemy's most effective weapon, especially when equipped with a flame-thrower. It was therefore expected that large armored formations would be used in the Homeland invasion. The Japanese forces were ill-equipped to meet such an attack due to marked inferiority in both tanks and antitank guns.90 This made

[611]

it essential to develop an aggressive antitank program relying on other weapons.

Experience in the Philippines and on Okinawa had demonstrated that the only effective means of combatting enemy tank superiority lay in a resort to mass special-attack operations. Manuals and directives issued to implement the Ketsu-Go plan therefore placed strong emphasis on the utilization of such tactics. All military units, as well as civilians, were to be trained in the use of the many different types of hand-carried mines and charges designed for such attacks.91

Second only to the emphasis laid on tokko tactics, the most important aspect of the Ketsu-Go plan and its implementing directives was the inclusion of the doctrine of an aggressive beach defense. This doctrine, in brief, called for the defending forces to make their decisive stand on the beach and in the coastal plain rather than on inland positions, no matter how favorable in theory the latter might be. The decision to do this stemmed from the following considerations:92

1. There was no assurance that Japanese firepower and assault weapons could successfully penetrate an enemy beachhead once it had expanded to the edge of the coastal plain.

2. The coastal zone contained all of the large key air bases.

The third unique feature of the Ketsu-Go plan was the extent to which the civilian population was to participate in the actual military defense of the Homeland. The plan called for a "National Resistance Program," the basic concept of which was that all able-bodied Japanese, regardless of sex, would be called upon to engage in battle.93 Should the enemy overrun any considerable part of the Homeland, his forces were to be beset from all sides by partisan operations. Each citizen was to be prepared to sacrifice his life in suicide attacks on enemy armored forces. In addition, civilians were to be used in large numbers for behind-the-lines duties such as air raid precautions, construction, transport, and evacuation.94

Thus, relying for the most part on the suicidal bravery, ardent patriotism, and fierce loyalty of the people, Japan prepared to wage the final decisive battle against an enemy far superior in both technical resources and manpower.

[612]

Go to

Last updated 1 December 2006 |